Book Excerpt: ‘The Bedrock of Generative AI’

Table of Contents

The following is an excerpt from my published book AI Primer for Business Leaders detailing how training data quality is the bedrock of generative AI tools. At the time I wrote this chapter, using synthetic data was not a proven training technique and would lead to model collapse.

The Bedrock of Generative AI: High Quality Data

The importance of high-quality source datasets cannot be understated. The utility of any generative AI solution will be built upon the source data acquired. Currently, datasets are sourced from anywhere and everywhere possible. As generative AI products are released and benchmarked, they often indicate a “dataset size” that can be thought of as the amount of source data used to make all future educated guesses in response to customer queries.

The totality of data available to train on is thought to be finite, or at the very least, yielding diminishing returns over time. Further, with the explosion of generative AI products, many public sources of data are updating their terms and conditions to protect their data from robotic scraping; other datasets are moving behind paywalls or being taken down altogether. This is one of the most rapidly changing areas of AI, and I predict private companies will need to leverage their internal private data to be competitive with their AI solutions.

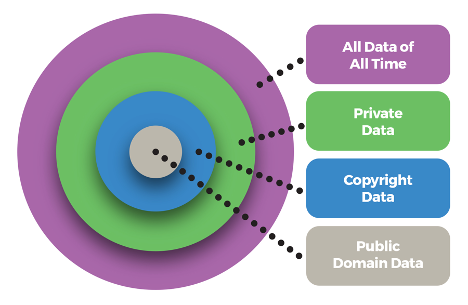

The value of this human-created data is reflected in the large deals signed for exclusive rights to use it for training. Having access to high-quality datasets is a competitive advantage that increases the value of any individual generative AI product. Complementing the generative AI lifecycle diagram, the available data for training can be thought of as a series of concentric circles that are rapidly expanding and contracting based on government legislation, litigation, and changes in terms of service by companies, with “All Data of All Time” being the upper bounds of available data and “Public Domain Data” being the smallest set of known data that is free to use in a commercial product.

Finding a way to catalogue and comprehend the totality of human published works has always been a distinctly human project, whether through a formal encyclopedia publication, the Google Books project, or crowdsourced via Wikipedia. A big promise of generative AI solutions is providing a way to surface relevant information from these vast data repositories in response to user queries—with the caveat that responses are an output reflective of predictions based on training data, not an authoritative one based on wisdom. I cover some examples of this in the “Personal Use of ChatGPT” Appendix and how it’s especially true as it pertains to “smushing” different source materials into one output.

To illustrate the importance of dataset selection, let’s revisit our librarian metaphor and presume the training dataset only contains American dessert recipe books published during the 1950s and 60s. Gelatin and Jell-O creations may dominate in this era, but would not hold up across the context of all recipes in history. If one set of material is overrepresented in training data—or worse, missing altogether—that will be reflected in the predictive outputs and limit the utility of the response or, worse, reflect the biases of the very human decision about which data to include.

Suddenly, the prompt “What desserts would you recommend making at home” returns Jell-O salad instead of chocolate chip cookies. This same concept applies to human biases and prejudices—a generative AI product is only as good as the training data it’s based on. If history belongs to the victors, then what of the fragmented perspectives of the losers? If they aren’t digitally represented in the training dataset, generative AI will be unable to provide any outputs referencing them.

Critical Thought: Dataset Limitations

Let’s revisit our librarian again to understand the limitations of readily available public data used for training in today’s generative AI products. With so much of the publicly available data coming from Anglo-Western society, current generative AI results skew toward that context. For example, in 2014, Amazon stopped work on an algorithmic approach to evaluating resumes for hiring as the underlying dataset was over-representative of white men with computer science degrees. Another documented bias in training data is prompting OpenAI’s DALL-E to create an image of a successful businessperson, to which it will likely return a Western perception of success: older white men in business suits.

Unlike a library that has a catalogue of materials, currently, there is no way to directly inspect the training dataset used by generative AI models, which are often cited as a competitive advantage or a trade secret. Researchers have been able to successfully use generative AI products to reproduce known copyrighted material, leading to the suspicion it is contained in the training datasets. There have been requests that companies make public both the underlying datasets and the training methodologies to ensure compliance with all laws and regulations. This will be critical to understanding any implications for new generative AI services built and brought to market.

In addition to not knowing what’s in the “library” of training data, generative AI products seem to struggle with sarcasm, satire, and contextual clues that keep them from distinguishing helpful fact from sarcastic answer. To be fair, humans fail at this as well—for example, sharing articles from The Onion as fact. A recent example cited in various news articles was a generative search result that adding glue to a cheese pizza makes it “stick better,” and eating rocks can improve your health. Aside from being unhelpful and potentially dangerous, it seems the generative AI “predicted” these as solutions based on specific Reddit posts likely present in its training dataset.

There is another danger to generative AI results: the Mandela effect, where the collective shared memory of a group supersedes the actual reality of the situation. In the aforementioned example, if enough people publish online content with incorrect information, generative AI will likely see this as correct. In the early days of web search, “Google bombing” was the attempt to mislead search results by associating keywords with specific websites or images; the future might contain “AI bombing,” where large datasets are sold seeded with misinformation in an attempt to influence outputs. A critical inspection of the data used for training is crucial for generating useful and correct generative outputs.

Finally, with generative AI tools becoming readily available for everyone a new slang term has popped up for AI generated content online: “slop.” It’s not quite spam, and it’s not human, but it exists. The creation of this content is poisoning the well of knowledge on Google Books and shutting down scientific journals overwhelmed by AI-generated submissions. Real human contributors are shut out as they try to compete with low-quality AI-generated content, and at the forefront of this adoption (from the consumer perspective) are spam websites trying to boost their search rank scores and grab ad dollars.

It’s important to identify the presence of AI-generated content in your own training datasets, as recursive training on AI generated content will eventually lead to model collapse. Some have suggested ending training datasets at 2021; this will quickly be outpaced by human discovery, and, because text generated by AI models is statistically correct, attempts at detecting it have so far eluded automation. At some point in the future, the majority of digital content will be produced by generative AI. When most readily available public data is AI-generated, knowing which data will make the most effective generative AI products will be a new role humanity needs to fill.

The Umbrella of “Fair Use” and Generative AI

There are a number of pending legal cases and ethical issues that need resolution pertaining to the inputs and outputs of generative AI that anyone should consider as they adopt generative AI solutions in their products, services, and work. Even though AI companies aren’t currently making training data public, it is presumed that the datasets are based on the digitization of a huge swath of humanity’s published works. These digital works range from being in the public domain to having strong copyrights with requirements for written permission from the copyright holder to use any portion thereof. Because generative AI companies are using robotic scraping and purchasing digital data to fuel their datasets, there is a clash between copyright holders and service providers. Historically, there has been deference to the use of robotic digital copying of material by companies, but the citing of “fair use” by OpenAI and others is currently under scrutiny.

Again, because it’s presumed that companies like OpenAI have scraped much of the publicly available web, they have been sued for copyright infringement by multiple trade groups. OpenAI has indicated in court filings that because its outputs are transformative of the inputs, this qualifies as fair use. However, the company has provided no mechanism by which copyright holders can opt out, identify their data in training sets, or even attempt to build a product using only data known to belong to the public domain.

OpenAI has also said that “limiting training data to public domain books and drawings created more than a century ago might yield an interesting experiment, but would not provide AI systems that meet the needs of today’s citizens.” Independent researchers have been able to use prompts to regenerate entire copyrighted works, calling into question whether OpenAI and others have respected existing copyright law by taking copyright content and incorporating it into their commercial product.

A few big tech firms have formed a lobbying group that seeks to educate legislators and consumers on the topic—in their favor, of course. In this material, they cite that one of the uses of programmatic “reading” is to provide insights and further advancement to the humans using that material. Thus far, courts have taken a permissive view of this learning model of copying, but it remains to be seen if that continues with these recent innovations in the generative AI field.

Harvard Business Review has a good summary of the what the courts are being asked to define, such as their interpretations of what constitutes a “derivative work” and the “transformative use of copyright material.” One way to circumvent all of these challenges is to only include data in the training sets that has known copyright heritage or to work with a generative AI service provider that agrees to take on the liability of any copyright infringement.

Copyright Holders and Compensation

Two themes have emerged from the various court cases currently navigating through the justice system. First is that corporations can identify and recognize that copyright holders can be negotiated with and compensated for their works, as we’ve seen previously with the compensation model change for actors, the transition from syndication to streaming of movies and television shows, and the streaming compensation in the music industry. Second is that the invention of a new transformation process does not negate or strip the rights of copyright holders to license that work for capital gain.

As it pertains to fair use, courts will need to decide if a for-profit company can programmatically copy all digital content and repackage it as a paid product irrespective of a copyright holder’s rights. Without legislative change or court rulings, it seems unlikely that corporations will provide a way for copyright holders to search datasets and prove that their content is being used and thus in need of citation/compensation. Many of these cases will need to be argued and settled to identify a new compensation model for copyright holders and to address the ethics of appropriate fair use.

Additionally, it seems awfully convenient that many of the first generative AI companies that have vacuumed up all of this public data are now calling for regulations and data protections after they’ve already acquired their commanding lead. How might a new company compete when all new data acquisition is met with large costs and purchase agreements? They key takeaway here is that source datasets may become a source of liability, and the surest way to avoid it is to only include data with clearly negotiated copyright license agreements.

Copyright © 2024 by James Rowe. From the book AI Primer for Business Leaders: Demystifying Generative AI. Reprinted by permission.

Significant Revisions

- Feb 6th, 2025 Originally published on https://jsr6720.github.io with uid 6E15C386-F20C-45DF-88A8-F8D5D738292F

Footnotes

In the published work, these are a combination of endnotes and footnotes. In this post, I’ve summarized them to just their links below.